The Historical Context of Beauty

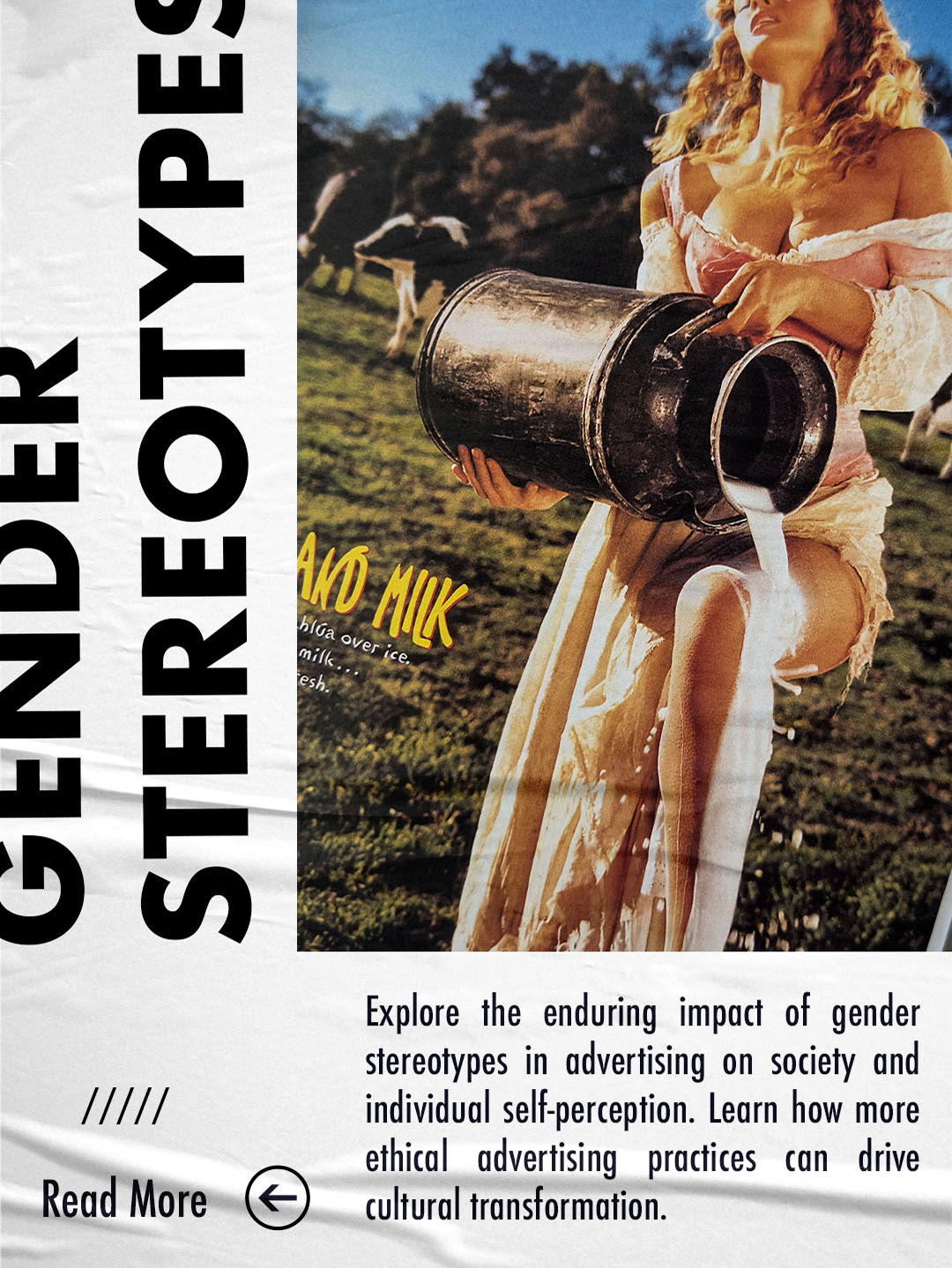

Historically, the concept of beauty has been exalted and pursued with fervor in both art and daily life, but this unrelenting quest often blinds us to the intrinsic value that resides in its counterpart—ugliness. The stringent adherence to universal beauty standards fails to acknowledge that these criteria are not only culturally constructed but have also fluctuated dramatically across different epochs and societies. This realization challenges us to reconsider the validity of a seemingly immutable concept like universal beauty, especially given its transient and ever-evolving nature.

In the modern era, the obsession with beauty appears even more pronounced, perhaps exaggerated, when placed in the broader tapestry of history. Despite this, the preoccupation endures, pushing us to find avenues to break free from the so-called cult of beauty. A potential escape could be found in a deliberate pivot towards what has been traditionally spurned: ugliness. Academically and culturally sidelined, ugliness is often hastily dismissed as merely the lack of beauty. Design critic Stephen Bayley confronts this neglect in his provocative work, Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything, proposing that ugliness is a rich, albeit underexplored, subject within artistic discourse, often avoided by artists due to its socially ascribed negative connotations.

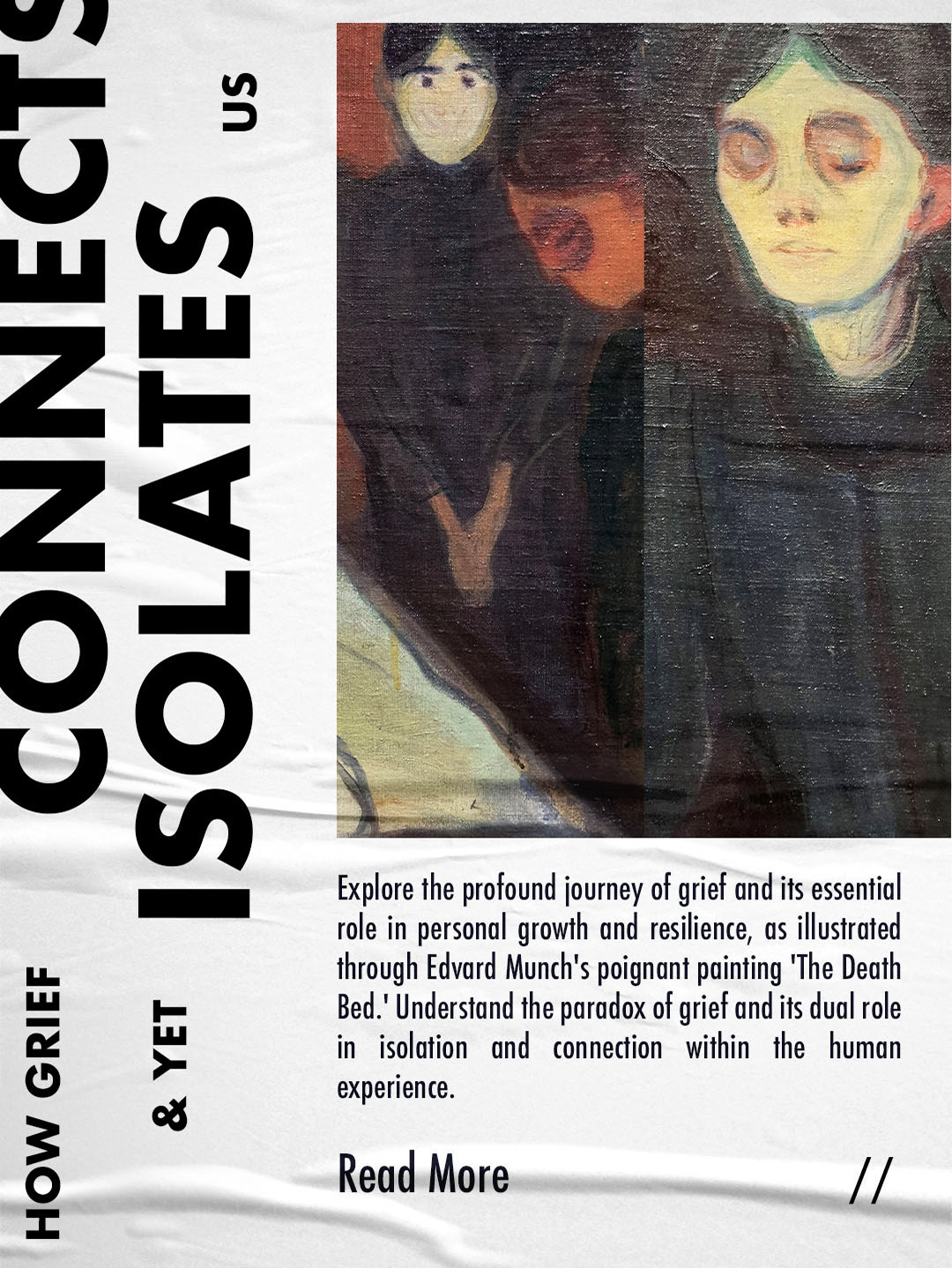

Art, however, transcends the simplistic production of beauty; it serves to reveal the subjective experiences of others, allowing viewers to perceive or empathize with perspectives foreign to their own. This revelation is not exclusive to traditionally beautiful artworks but can be significantly more penetrating in pieces that consciously incorporate elements of ugliness. For many individuals, hiding or correcting what is deemed ugly constitutes a lifelong struggle, yet it is precisely in artworks that expose and explore these aspects where a unique kind of dignity and undeniable truth is found. Quentin Matsys’s The Ugly Duchess, thought to depict a woman afflicted with a rare form of Paget’s disease, stands as a poignant example of this. Similarly, David Lynch’s film The Elephant Man tells the story of John Merrick, whose profound humanity and dignity challenge the societal gaze that equates physical deformity with worthlessness, eliciting a deep emotional and introspective response from audiences.

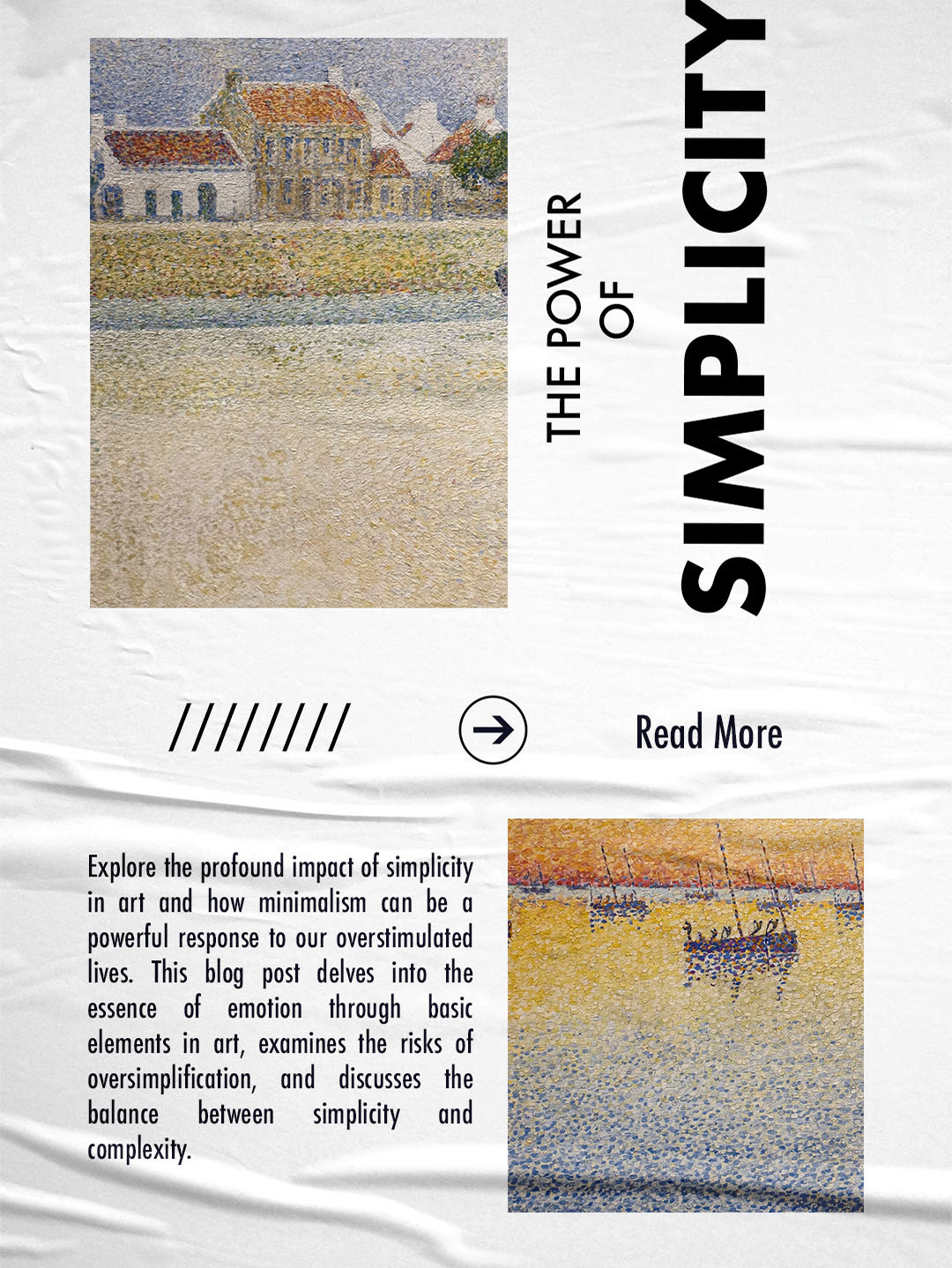

By critically examining these representations of ugliness, we are invited to question our own biases and the societal norms that shape them. The continued exploration of ugliness in art not only diversifies our aesthetic experiences but also enriches our understanding of human conditions, pushing us to confront uncomfortable truths about how we define and value beauty and its supposed opposite.