Swabian, Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family, about 1470, The National Gallery, London, Photo by Kianoush Poyanfar

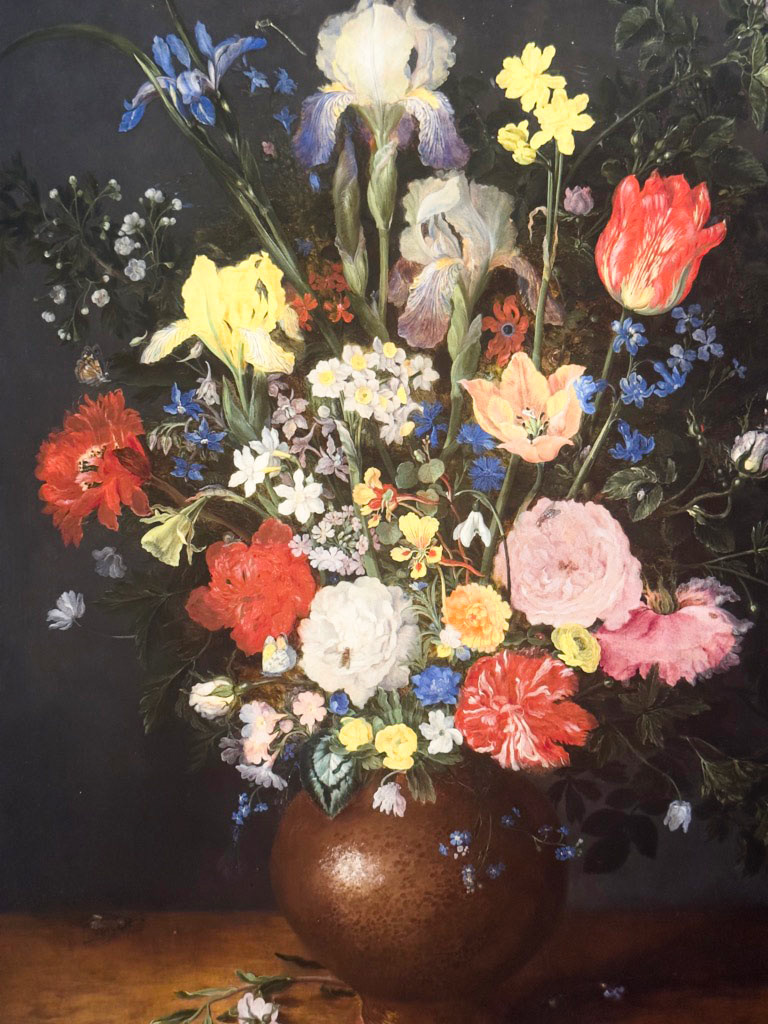

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Bouquet in a Clay Vase, about 1609, The National Gallery, London, Photo Kianoush Poyanfar

Introduction:

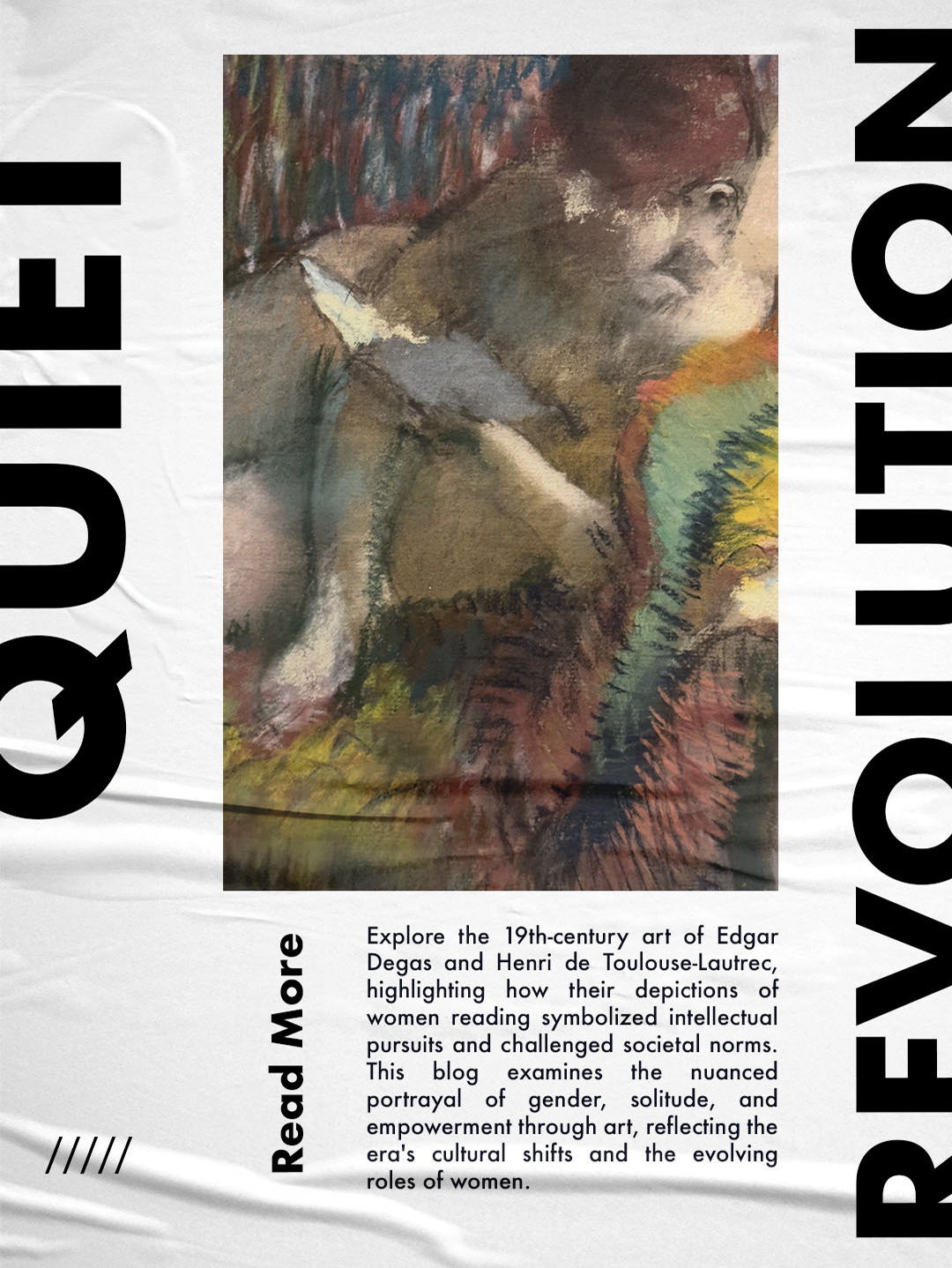

In the vivid, colorful expanses of floral paintings, every element holds meaning—right down to the smallest insect. This blog post explores the intricate role of insects in artworks, focusing on the meticulous details artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder incorporated into their floral masterpieces, and drawing a parallel to another intriguing use of insects in art, as seen in the "Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family" by an unnamed Swabian artist from the late 15th century.

Insects as a Symbol of Skill and Symbolism

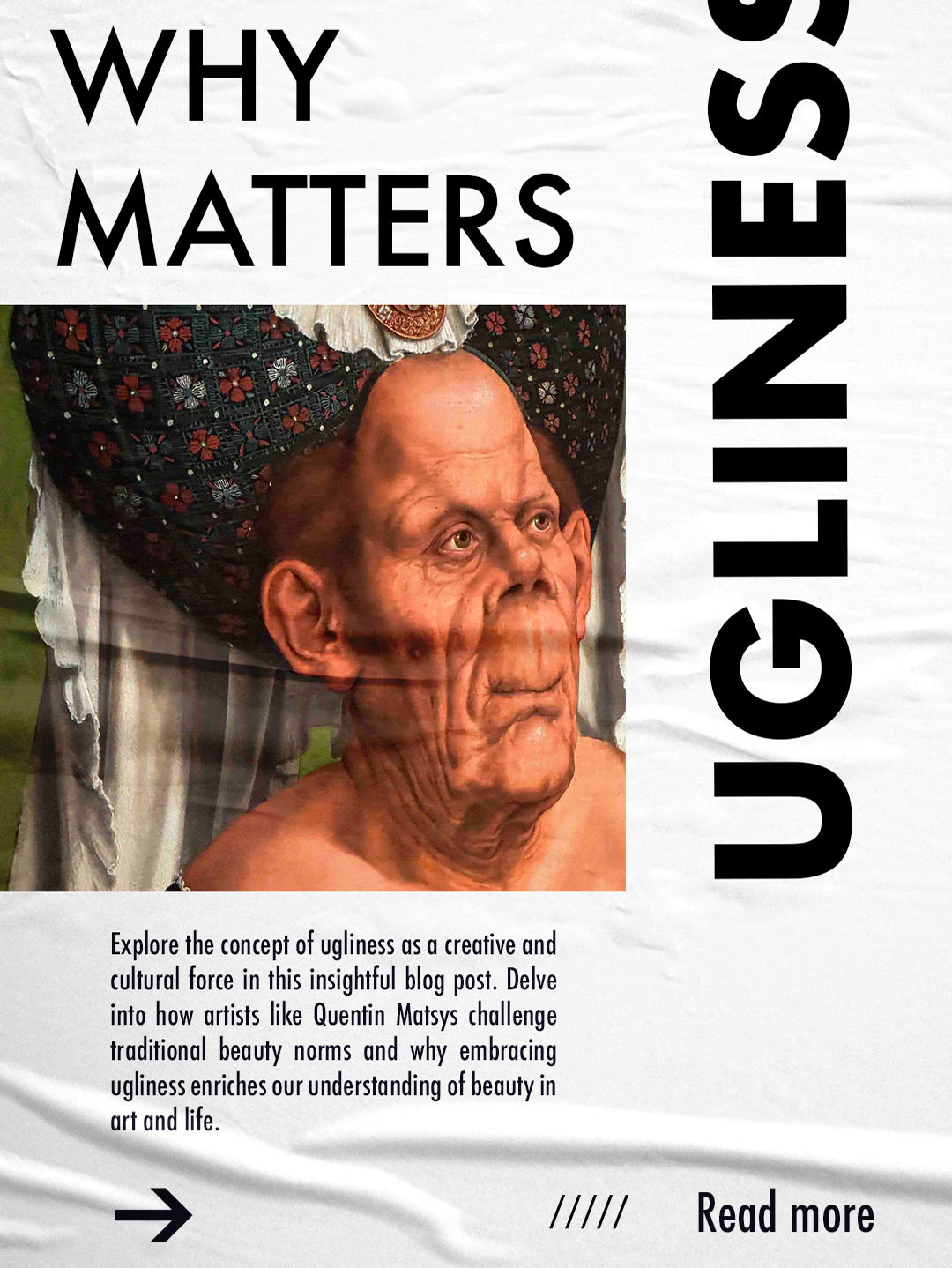

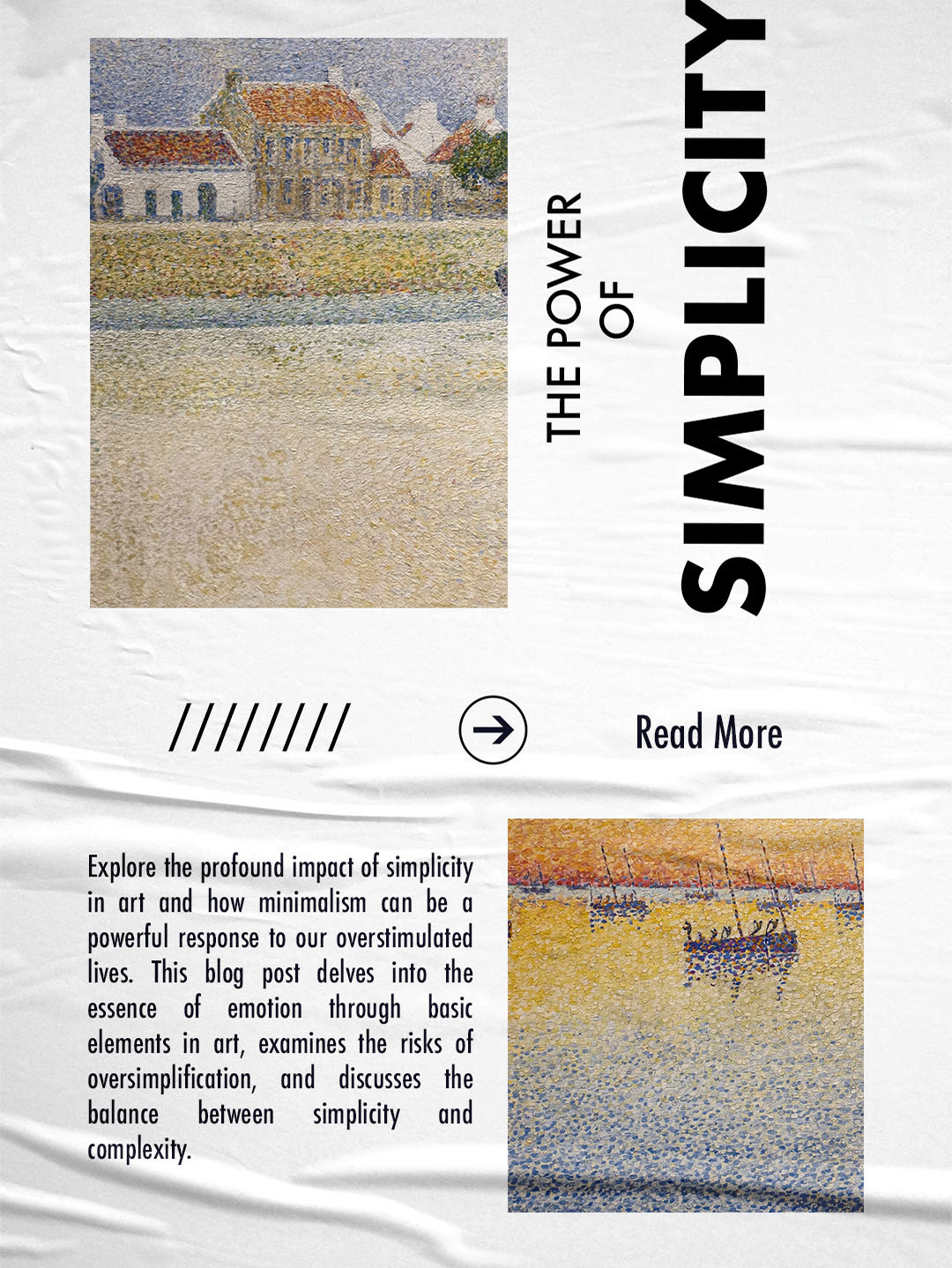

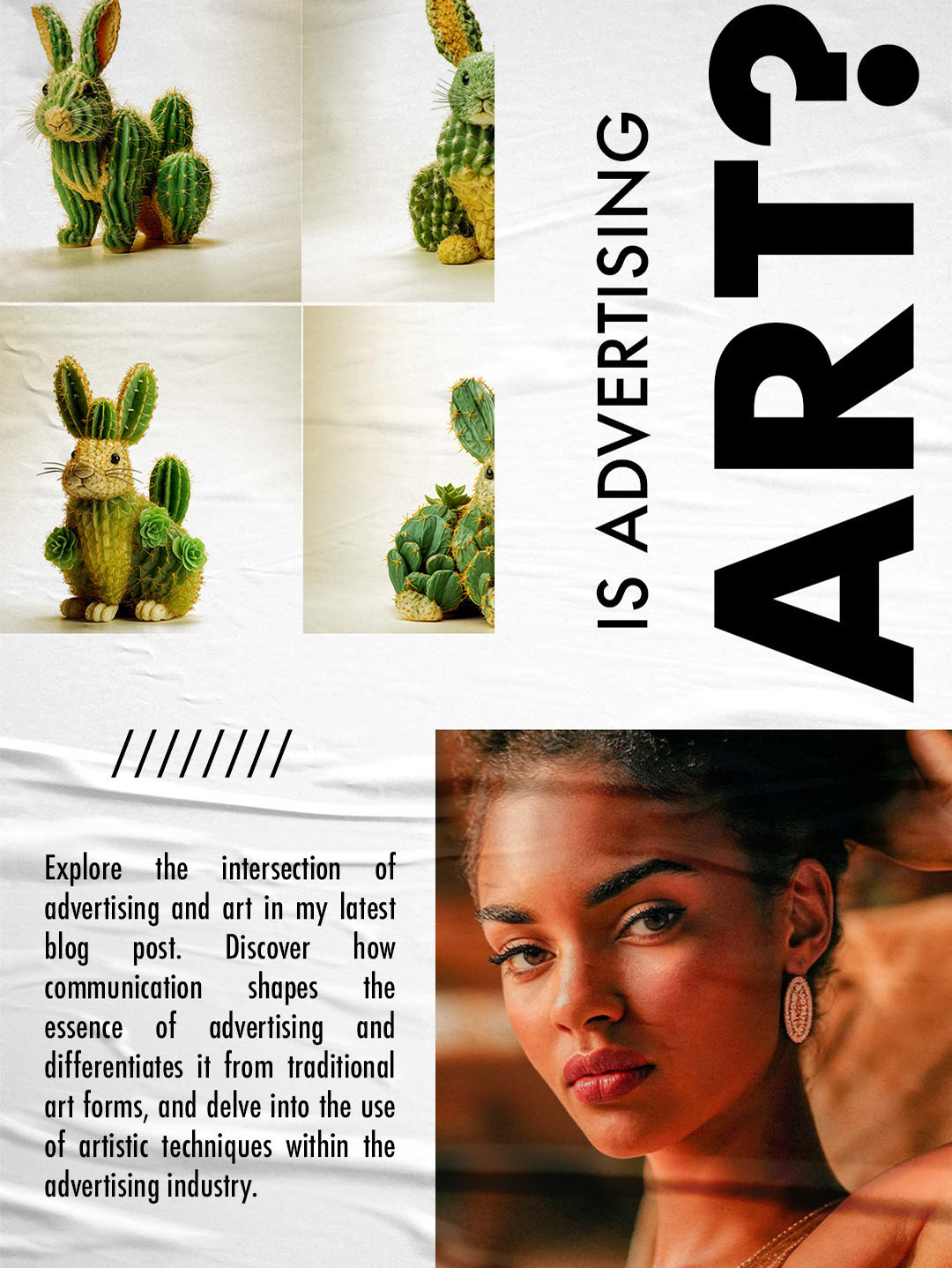

Jan Brueghel the Elder's painting, "Bouquet in a Clay Vase" (circa 1609), stands as a testament to the multifaceted layers of meaning that can be conveyed through the art of still life, especially in the inclusion of insects among the vivid floral arrangements. Brueghel, renowned for his pioneering contributions to the flower still life genre, did more than just depict botanical accuracy; he captured an entire microcosm of life within the confines of a clay vase. His work weaves a complex narrative that speaks not only to the sensory delights of its vibrant blooms but also to profound philosophical themes.

In Brueghel’s composition, each insect—be it a bee, butterfly, or beetle—serves a purpose beyond mere aesthetic enhancement. These creatures, often overlooked in their everyday contexts, are depicted with astonishing detail, elevating them to a level of significance that challenges the viewer to consider their role in the natural cycle. Traditionally, insects in art have been symbolic of decay and the ephemeral nature of life. This recurring theme juxtaposes the transient, fleeting moments of beauty captured by the lifespan of flowers with the perpetual cycle of birth and decay in nature. Thus, the insects fluttering amongst the petals underscore a stark reminder: all life, no matter how beautiful, is temporary.

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Bouquet in a Clay Vase, about 1609, The National Gallery, London, Photo Kianoush Poyanfar

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Bouquet in a Clay Vase, about 1609, The National Gallery, London, Photo Kianoush Poyanfar

However, this interpretation of decay contrasts with another, perhaps more uplifting perspective. While some may view the presence of insects as a morbid reminder, others might see them as symbols of resilience and renewal. Insects are, after all, critical pollinators within ecosystems. Their interaction with flowers is not merely one of fleeting beauty but a vital activity that leads to growth and reproduction—nature's way of ensuring that life goes on. This dual symbolism could be seen as a celebration of life’s continuity rather than merely a memento mori.

Moreover, the very act of painting such detailed and dynamic still lifes could also be seen as Brueghel’s defiance against the decay he depicts. Art itself acts as a preservative, a way to halt time and capture the ephemeral forever. In this light, Brueghel's work can be interpreted as an optimistic assertion of the human capacity to generate lasting beauty and meaning, even in the face of nature’s inexorable cycles.

Critics and art historians might argue about the predominance of one theme over the other. Some may find the inclusion of insects to be a grim commentary on the vanity of earthly delights, emphasizing that decay is all that awaits. Others might insist on a more balanced view, where decay is acknowledged but so is the essential role of renewal and continuity in the natural world.

In contemplating Brueghel's "Bouquet in a Clay Vase," we find a rich tableau that invites multiple interpretations, each offering its own insights into the human condition. Whether seen as a sober reflection on mortality or a celebration of life's resilience, Brueghel's intricate interplay between flora and fauna remains a profound, multifaceted meditation on the beauty and brutality of the natural world. This duality not only enriches our understanding of Brueghel’s art but also enhances our appreciation of the complexity of life itself.

Rachel Rush, Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Marble Ledge, 1710, The National Gallery, London, Photo by Kianoush Poyanfar

Rachel Rush, Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Marble Ledge, 1710, The National Gallery, London, Photo by Kianoush Poyanfar

The Fly on the Headdress: Symbolism and Skill in Renaissance Portraiture

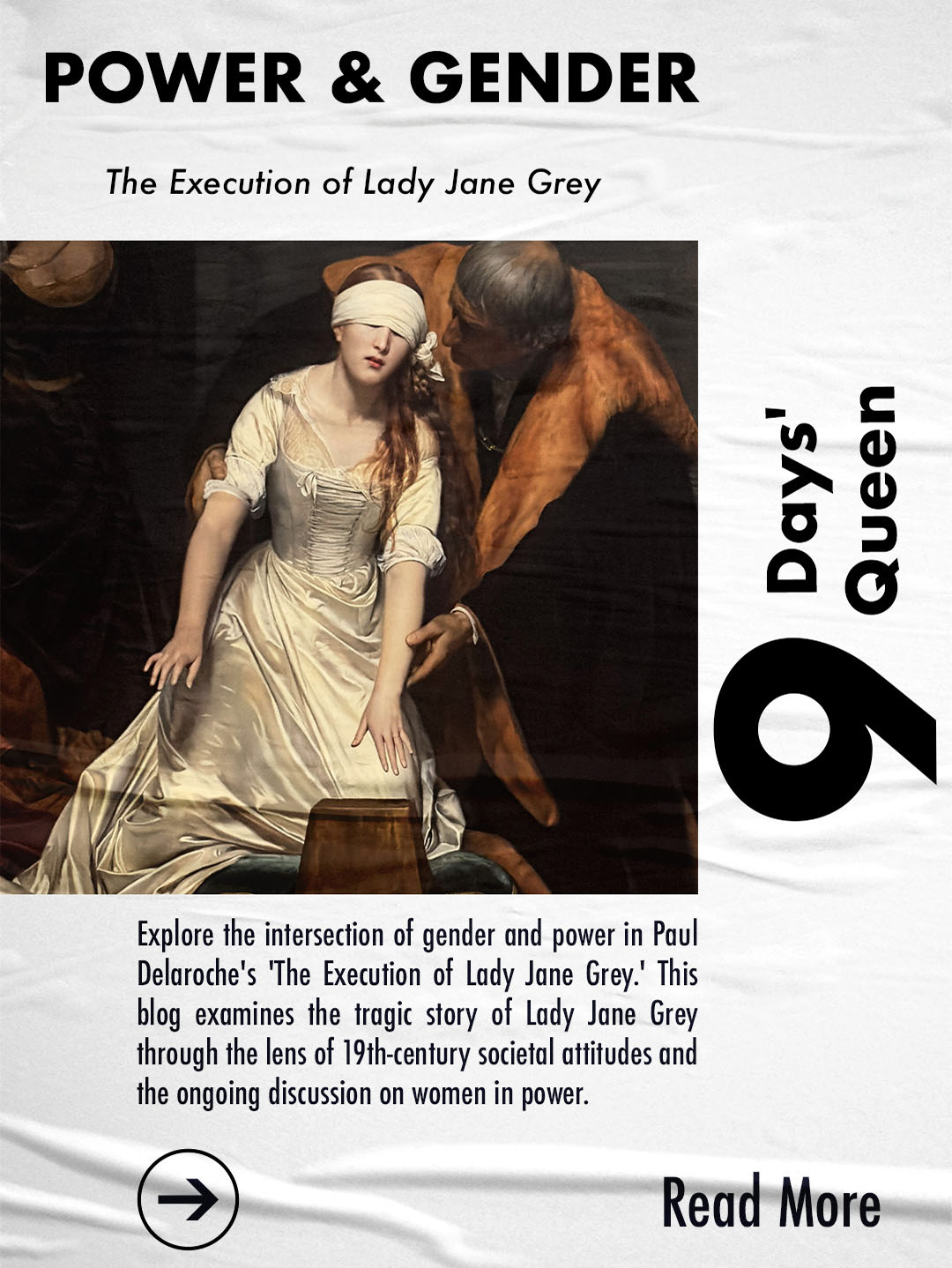

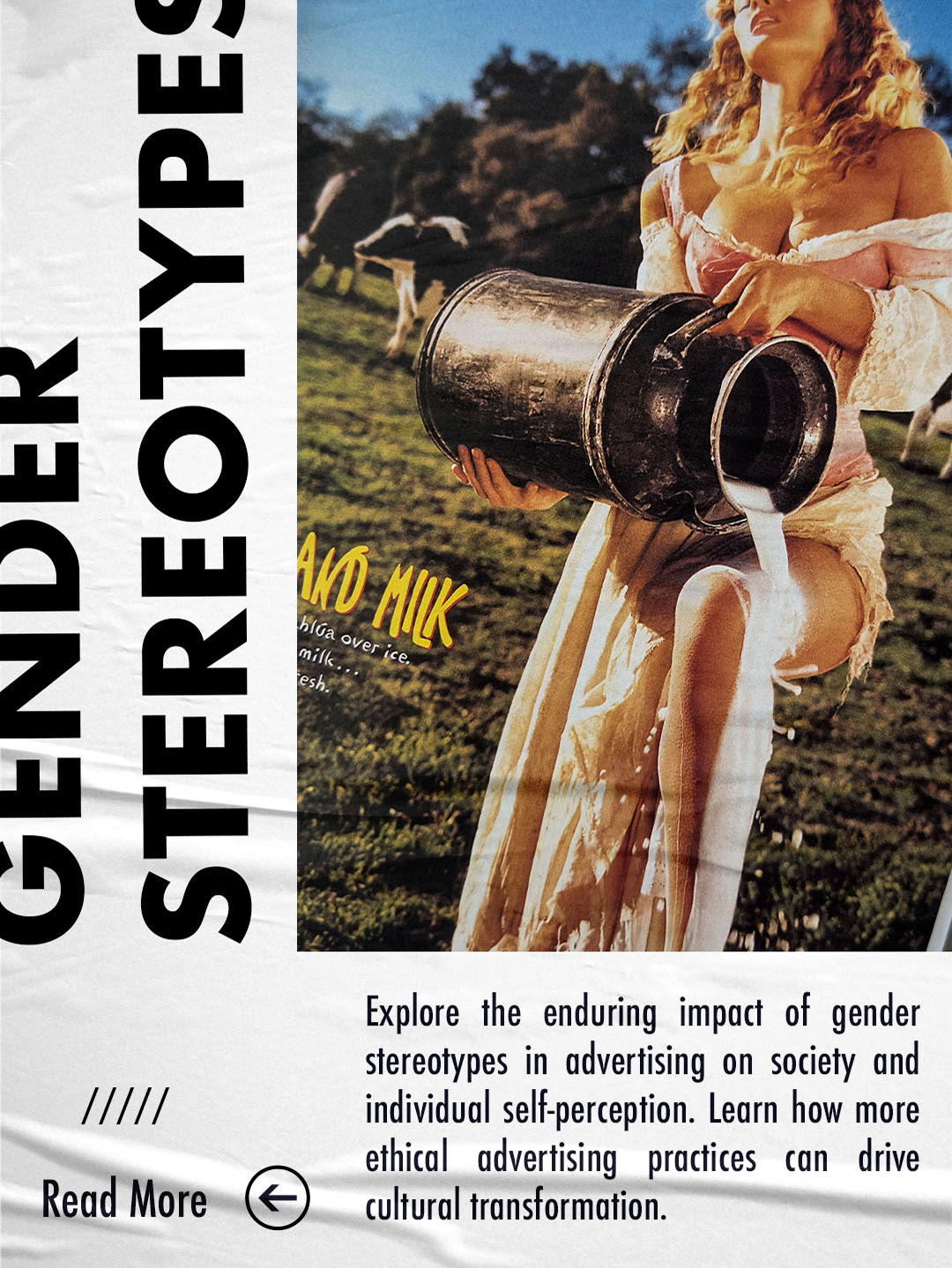

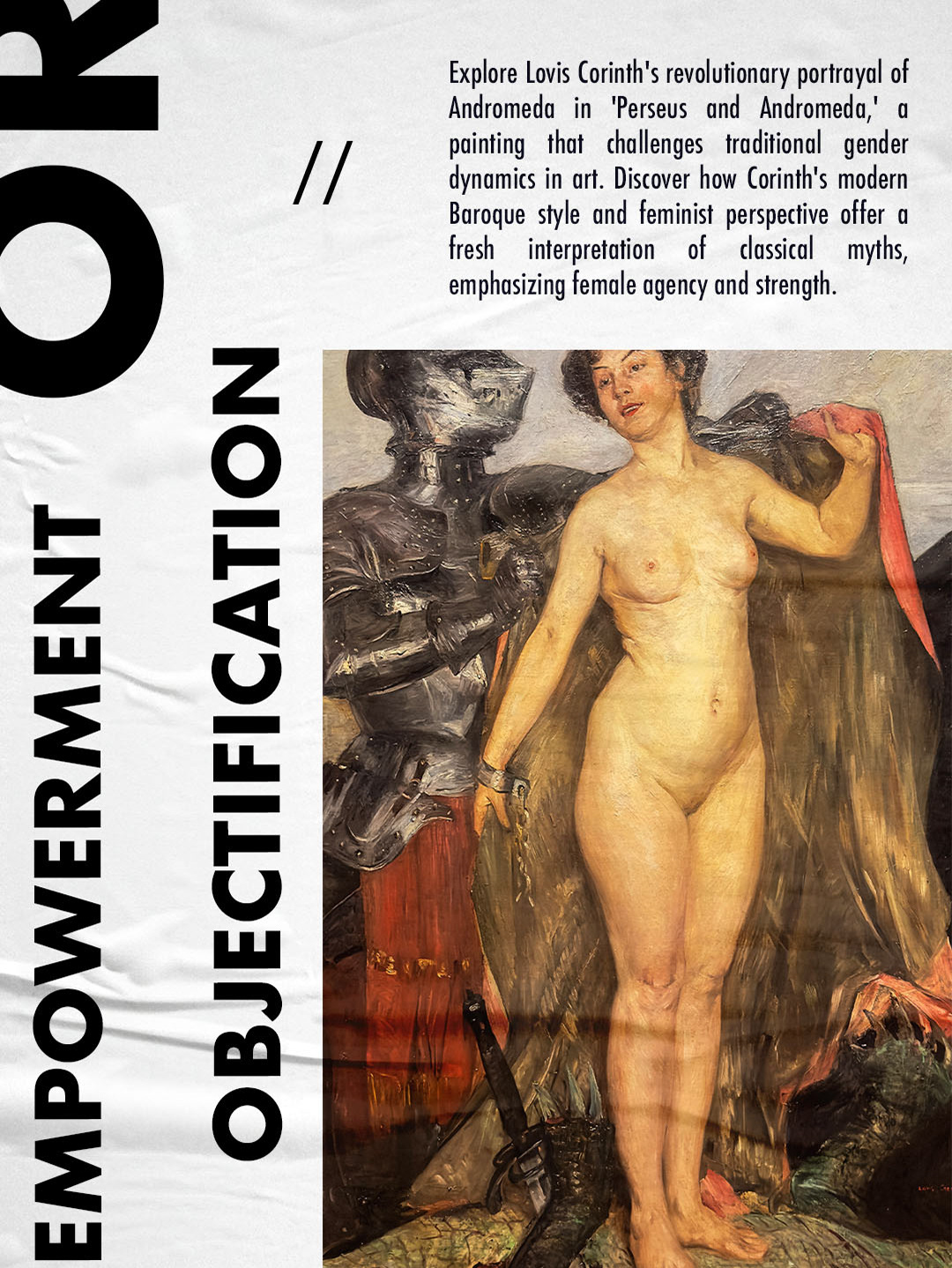

The "Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family" (circa 1470) provides a fascinating glimpse into the complex interplay between artistry and symbolism, particularly through the subtle inclusion of a fly on the woman’s headdress. This detail might appear minor, yet it holds significant weight in the interpretation of the painting's deeper meanings. The fly, while small and easily overlooked, carries with it profound connotations that enrich our understanding of the artwork.

In this portrait, the presence of the fly can indeed be seen as an emblem of mortality. Its inclusion on the headdress of the noblewoman—a place usually reserved for ornaments that signify status or beauty—introduces a jarring note of realism in an otherwise idealized representation. This could be interpreted as a reminder of the inevitability of death, suggesting that no amount of social standing or wealth can shield one from the universal fate of all living things. This theme of memento mori, common in art throughout history, is subtly yet powerfully conveyed through the inclusion of such a mundane and typically unwelcome creature.

However, the portrayal of the fly might also celebrate the artist’s virtuosity in capturing such minute detail that it could easily be mistaken for reality. This interpretation shifts the focus from the symbolic to the technical prowess of the artist. The ability to render details so lifelike that they can deceive the viewer is a hallmark of skilled craftsmanship and was particularly valued during the Renaissance period. This skill not only served aesthetic purposes but also acted as a visual trick that could engage and amuse sophisticated patrons.

Yet, there is another dimension to consider, one that contrasts with the somber interpretation of the fly as a symbol of mortality. Some art historians propose that rather than simply serving as a memento mori, the inclusion of such elements could also reflect a more nuanced understanding of life and death. Rather than a bleak reminder of death, the fly could symbolize resilience and persistence, qualities intrinsic to many insects that enable them to thrive in diverse and often harsh environments. In this context, the fly is not just a harbinger of death but a testament to survival and adaptation.

Additionally, the fly's presence in the painting could be viewed through a more philosophical lens, suggesting the coexistence of beauty and decay, nobility and the mundane, life and death. This dual presence might encourage viewers to appreciate the full spectrum of existence, prompting a deeper reflection on the human condition and the natural world's interconnected cycles.

Each of these interpretations offers a distinct perspective on the meaning behind the "Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family." Whether seen as a symbol of mortality, a display of artistic skill, or a broader philosophical statement, the inclusion of the fly transforms a traditional portrait into a rich canvas of potential meanings and interpretations, inviting viewers to look beyond the surface and engage with the deeper existential themes it subtly presents.

Swabian, Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family, about 1470, The National Gallery, London, Photo by Kianoush Poyanfar

Swabian, Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family, about 1470, The National Gallery, London, Photo by Kianoush Poyanfar

Conclusion

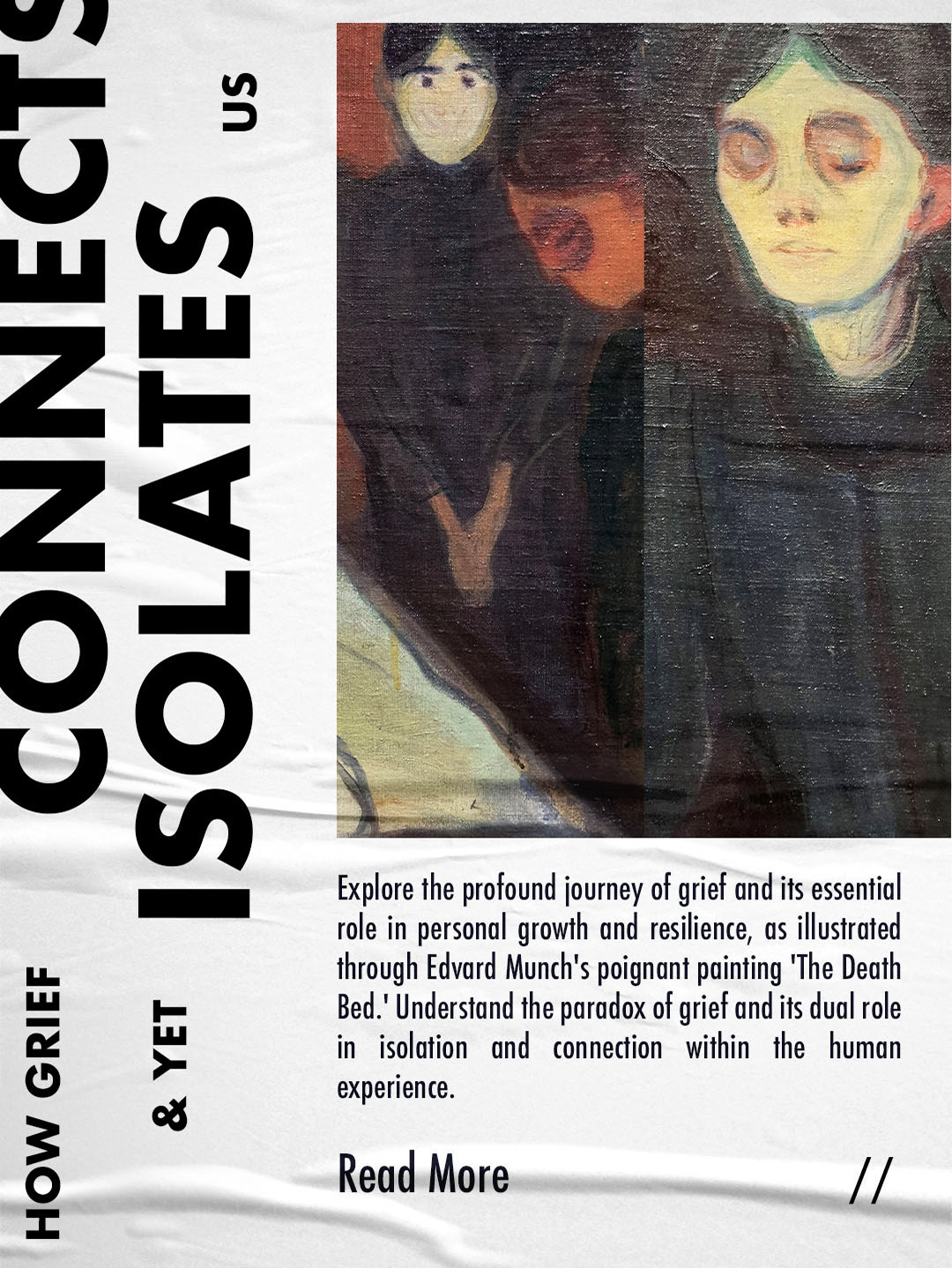

The practice of embedding insects and other elements of the natural world in art, as exemplified by Jan Brueghel the Elder and the anonymous Swabian artist of the "Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family," offers a profound reflection on the roles of art and artists across different periods. These details not only serve as a testament to the artists' technical skills and observational prowess but also as conduits for deeper symbolic meanings, reflecting the cultural, philosophical, and scientific preoccupations of their times.

In Brueghel's vibrant floral arrangements, every insect tells a story of decay and renewal, echoing the Baroque obsession with the vivacity and transience of life. Meanwhile, the subtle inclusion of a fly and a forget-me-not in the Swabian portrait speaks to the Northern Renaissance's introspective character, weaving themes of mortality and memory into the fabric of daily life. These artworks challenge us to look beyond the surface, to see the intersections of life's beauty and its inevitable end.

Critically, while some may argue that such symbols are prone to overinterpretation, this discourse itself is valuable. It highlights the dynamic nature of art interpretation and underscores the importance of historical and cultural context in shaping our understanding of these works. Moreover, it reminds us that art is not static; it is a living conversation across the ages, inviting each generation to rediscover and reinterpret its meanings.

As we continue to study these intricate creations, we are reminded of the enduring power of art to engage, provoke, and inspire. The detailed depiction of nature in these masterpieces does more than capture the eye—it captures the imagination, prompting us to explore the rich tapestry of human experience, interwoven with the natural world. Thus, through the minute wings of a fly or the delicate petal of a flower, we are invited into a larger dialogue—one that spans centuries and continues to resonate with contemporary audiences seeking connection and meaning in the artistic expressions of the past.